| OPIC

|

|

CIPO

|

| LE REGISTRAIRE DES MARQUES DE COMMERCE

THE REGISTRAR OF TRADE-MARKS

|

||

Citation: 2019 TMOB 26

Date of Decision: 2019-03-27

IN THE MATTER OF OPPOSITIONS

|

|

Rothmans, Benson & Hedges Inc.

|

Opponent

|

| and

|

||

|

|

Imperial Tobacco Products Limited

|

Applicant

|

|

|

1,580,250 and 1,580,255 both entitled PURPLE PACKAGE DESIGN

|

Applications

|

introduction

[1]

Rothmans, Benson & Hedges Inc. (the Opponent) opposes registration of the trade-marks both entitled PURPLE PACKAGE DESIGN (reproduced below) that are respectively the subject of application Nos. 1,580,250 and 1,580,255 based upon use in Canada since August 2011 in association with “manufactured tobacco products, namely cigarettes” (the Goods) filed by Imperial Tobacco Products Limited (the Applicant):

| Application No. 1,580,250

(hereinafter sometimes referred to as the '250 Application)

|

Application No. 1,580,255

(hereinafter sometimes referred to as the '255 Application)

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Description: The trade-mark consists of the colour purple applied to the visible surface of the particular packaging as shown in the attached drawing. The drawing has been lined for colour.

|

Description: The trade-mark consists of the colour purple applied to the visible surface of the particular packaging as shown in the attached drawing. The drawing has been lined for colour.

|

[2]

The only difference between the two applications is that the '250 Application depicts a three-dimensional design, while the '255 Application depicts a two-dimensional one. Unless indicated otherwise, I will collectively refer to these two design marks as the Mark.

[3]

The oppositions were brought under section 38 of the Trade-marks Act, RSC 1985, c T‑13 (the Act), and originally raised grounds of opposition based upon sections 2 (non-distinctiveness); 12 (non-registrability); 16 (non-entitlement); and 30 (non-conformity) of the Act.

[4]

For the reasons that follow below, I find the applications ought to be refused.

The record

[5]

The applications for the Mark were both filed on June 1, 2012 and were advertised for opposition purposes in the Trade-marks Journal on January 9, 2013 ('250 Application) and December 26, 2012 ('255 Application).

[6]

The applications were opposed by the Opponent by way of statements of opposition filed with the Registrar on May 23, 2013. In response to the Applicant’s request for an interlocutory ruling, by way of Office letters dated January 16, 2014 ('250 Application), and January 23, 2014 ('255 Application), the Registrar struck the section 16 ground of opposition and one of the non-distinctiveness grounds of opposition pleaded respectively at paragraph 13 and 14(d) of each of the statements of opposition. Consequently, no section 16 ground of opposition remains in either case. Unless indicated otherwise, I will use the singular to refer to the two statements of opposition as they are essentially identical (except for the identification of the applied-for trade-mark and some of the section 30 grounds of opposition). For ease of reference, I reproduce the grounds of opposition as pleaded by the Opponent in respect of the '250 Application and the '255 Application respectively, at Schedules A and B to my decision.

[7]

The Applicant filed and served a counter statement in each case denying the grounds of opposition set out in the statement of opposition.

[8]

In support of each of its oppositions, the Opponent filed the following documents:

- The affidavit of Mary P. Noonan, a trade-mark searcher employed by the Opponent’s trade-marks agent, sworn on May 30, 2014 (the Noonan affidavit);

- The affidavit of David Morrison, an associate lawyer employed by the Opponent’s trade-marks agent, sworn on May 30, 2014 (the Morrison affidavit);

- A certified copy of the file history of the '250 Application; and

- A certified copy of the file history of the '255 Application.

[9]

I will use the singular to refer to the two affidavits of each of these deponents, as they are essentially identical. An order for the cross-examination of all affiants issued but no cross-examinations were conducted.

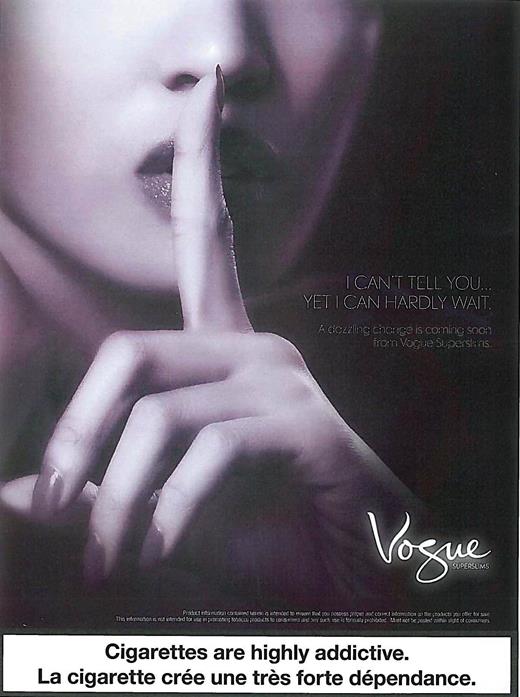

[10]

In support of each of its applications, the Applicant filed the following documents:

- The affidavit of Jason Dacayanan, the Brand Manager for, inter alia, the VOGUE brand of cigarettes at Imperial Tobacco Canada Limited (ITCan), a related company to the Applicant, sworn on December 22, 2014 (the Dacayanan affidavit);

- The affidavit of Jayson B. Dinelle, a law clerk for the Applicant’s trade-marks agent, sworn on December 23, 2014 (the Dinelle affidavit); and

- The affidavit of Gay Owens, a trade-mark searcher for the Applicant’s trade-marks agent, sworn December 23, 2014 (the Owens affidavit).

[11]

I will use the singular to refer to the two affidavits of each of these deponents, as they are essentially identical. Mr. Dacayanan was cross-examined on his affidavit and the transcript of his cross-examination and the responses to the undertakings made at the time of his cross-examination are on the record.

[12]

Both parties filed written arguments in each case and attended an oral hearing.

[13]

On July 26, 2018, over two weeks after the oral hearing, the Opponent filed in both files a request for leave to file an amended statement of opposition. By way of letter dated July 31, 2018, the Applicant objected to the Opponent’s request in both files. The Applicant further advised that it had no objection to the Registrar addressing the Opponent’s leave request as part of the Registrar’s decision of the opposition proceedings on the merits. Accordingly, I will first address the Opponent’s leave request below.

preliminary remarks

Request for leave to file an amended statement of opposition

[14]

As set out in the practice notice entitled Practice in Trade-marks Opposition Proceedings, leave to amend a statement of opposition will only be granted if the Registrar is satisfied that it is in the interests of justice to do so having regard to all the surrounding circumstances including: the stage the opposition proceeding has reached; why the amendment was not made earlier; the importance of the amendment; and the prejudice which will be suffered by the other party.

[15]

In its leave request, the Opponent submits that “out of an abundance of caution”, it is seeking leave to amend each of its statements of opposition to:

…

clarify the previously-pleaded [section] 30(b) and [section] 2 non-distinctiveness grounds of opposition by making clear that these grounds of opposition include the allegation that the purported use of the mark at issue under license does not accrue to the Applicant’s benefit. These amendments are intended to reflect and be consistent with the Opponent’s position on this issue demonstrated throughout these proceedings as set out in detail in the Opponent’s written arguments.

[16]

However, as stressed by the Applicant in its letter dated July 31, 2018 objecting to the Opponent’s leave request, the Opponent’s grounds of opposition under section 30(b) and section 2 of the Act in each of the present cases clearly set out grounds of opposition that relate to the nature of the trade-mark itself and the ability of the trade-mark depicted in the application to function as a trade-mark (e.g. the Opponent alleges that the trade-mark is not visible in the manner claimed in the application, was merely ornamental, was merely a background colour, etc.) [see paras 5, 6 and 14 of the statements of opposition reproduced in Schedules A and B].

[17]

I agree with the Applicant that there is no reasonable way to read the above-referenced paragraphs of the statement of opposition as alleging a ground of opposition based on unlicensed use of a trade-mark which does not accrue to the Applicant pursuant to section 50 of the Act. The amendments sought by the Opponent fundamentally change the nature of the pleaded grounds of opposition by adding completely new and different grounds of opposition.

[18]

As reminded by the Applicant both at the oral hearing and in its letter, there is a substantial body of jurisprudence in which opponents, as in the present cases, have attempted to raise a licensing issue late in the proceeding after the evidence phase is closed, without including any reference to that ground in its statement of opposition [see for example Apotex Inc v Smithkline Beecham Corporation (2005), 54 CPR (4th) 104 (TMOB); and Mattel U.S.A. Inc v 3894207 Canada Inc (2002), 23 CPR (4th) 395 (TMOB)]. In each case, consideration of the licensing issue was refused by the Registrar as having not been properly pleaded in the statement of opposition.

[19]

As stressed by the Applicant, the prejudice to the Applicant is readily apparent and there is no later stage in the opposition proceeding to make such a leave request. As indicated above, the request was made over two weeks after the oral hearing of the matters. As noted by the Applicant, the Opponent could have sought leave to amend its statement of opposition after conducting the cross-examination of the Applicant’s affiant, or after receiving the Applicant’s written answers to undertakings made during the cross-examination. Had the Opponent pleaded at that time that the licensed use of the Mark put into evidence by the Applicant’s own affiant did not accrue to the Applicant’s benefit, the Applicant might have filed evidence to sustain the opposite view. I agree with the Applicant that the Registrar’s decisions in Spin Master Ltd v George & Company, LLC, 2015 TMOB 157 and Karma Candy Inc v Cadbury UK Limited, 2013 TMOB 119 are particularly instructive, as in these cases, the opponent sought leave to include additional grounds of opposition during and after the oral hearing, respectively, and in both cases leave to amend was refused.

[20]

In the present cases, it is not in the interests of justice to grant leave to the Opponent to amend its statement of opposition as requested because the prejudice and delay factors outweigh the importance of the amendment. In view of all of the foregoing, the Opponent’s request for leave to amend its statement of opposition is refused in each case.

Past opposition proceedings between the parties

[21]

The parties to the present proceedings are not strangers. They are direct competitors in the Canadian cigarette market and have been involved in opposition proceedings concerning the Applicant’s trade-mark application Nos. 1,317,127 (now TMA908,657) and 1,317,128 (now TMA908,626) both entitled ORANGE PACKAGE DESIGN, which applications were substantively identical to the present ones in terms of the manner of depiction and description of the applied-for trade-mark, other than the colour claimed and specific shape depicted, and which were opposed by the Opponent in the present cases as well as JTI MacDonald TM Corp. on similar grounds of opposition. The Registrar’s decisions dismissing both of the Opponent’s oppositions and JTI MacDonald TM Corp.’s oppositions [see Rothmans, Benson & Hedges v Imperial Tobacco Products, 2012 TMOB 226 (the 226 Decision); JTI-Macdonald TM Corp v Imperial Tobacco Products Limited, 2012 TMOB 116 (the 116 Decision); and JTI-Macdonald TM Corp v Imperial Tobacco Products Limited, 2012 TMOB 117 (the 117 Decision)] were upheld by the Federal Court in Rothmans, Benson & Hedges, Inc v Imperial Tobacco Products Limited, 2014 FC 300 (the FC 300 Decision) and JTI-Macdonald TM Corp v Imperial Tobacco Products Limited, 2013 FC 608 (the FC 608 Decision), as well as by the Federal Court of Appeal in Rothmans, Benson & Hedges, Inc v Imperial Tobacco Products Limited, 2015 FCA 111 (the FCA 111 Decision) (sometimes hereinafter collectively referred to as the ORANGE Decisions).

[22]

Not surprisingly, the Applicant relies heavily on the ORANGE Decisions in the present cases. However, these prior decisions are not necessarily determinative of the issues. Suffice it to say that each case rests on its own merits. That being said, I will adopt some of the reasoning in the ORANGE Decisions where I consider it appropriate to do so.

the parties’ respective burden or onus

[23]

The Applicant bears the legal onus of establishing, on a balance of probabilities, that its application complies with the requirements of the Act. However, there is an initial evidential burden on the Opponent to adduce sufficient admissible evidence from which it could reasonably be concluded that the facts alleged to support each ground of opposition exist [see John Labatt Ltd v Molson Companies Ltd (1990), 30 CPR (3d) 293 (FCTD) at 298].

Overview of the evidence

The Opponent’s evidence

The Noonan affidavit

[24]

The Noonan affidavit contains printout results of Ms. Noonan’s search of the Canadian Trade-marks Register for “any trade-mark applications and registrations on the Register for single colour marks without words which are on the record for tobacco and tobacco related wares”. Particulars of 10 such applications and registrations are provided in Exhibit MN-1.

The Morrison affidavit

[25]

The Morrison affidavit contains photographs of a VOGUE slims cigarette package which he purchased from International News located at 130 King Street West, in Toronto, Ontario, together with a copy of the receipt for such purchase [Exhibits DM-1 and DM-2].

[26]

The Morrison affidavit also contains printouts of Canadian rules and regulations for tobacco product information and labelling, providing for, among other things, the mandatory presence of various health warning labels to be placed on all cigarette packages sold in Canada [Exhibits DM-3 to DM-8].

The Applicant’s evidence

The Dacayanan affidavit

[27]

In the introductory paragraphs of his affidavit, Mr. Dacayanan provides some background information about the ownership and licensing of the VOGUE Superslims family of cigarettes. He explains that pursuant to a license agreement between ITCan and its wholly owned subsidiary Imperial Tobacco Products Limited (ITPL), ITCan is “licenced to use ITPL’s [trade-marks] in association with the manufacture and sale of tobacco products” and ITPL has “direct and indirect control of the character and quality” of such products “manufactured and sold by ITCan under the licence”. Mr. Dacayanan attaches as Exhibit A to his affidavit a redacted copy of this licence agreement made on February 1, 2000 [para 2].

[28]

Mr. Dacayanan asserts that pursuant to this licence, ITCan “has manufactured or has had manufactured VOGUE brand cigarettes, including the VOGUE Superslims family of cigarettes sold in Canada since at least as early as August 2011”. He asserts that the VOGUE Superslims family of cigarettes is marketed and sold in Canada by ITCan via its distributor Imperial Tobacco Company Limited (ITCL) to cigarette retailers, and sometimes through wholesalers [para 3].

[29]

As an aside here, despite the fact that the license agreement referred to above under Exhibit A was not amended to expressly include the applied-for Mark launched in August 2011, I am prepared to accept that the Applicant has had, at all times, the requisite control over the character and quality of the goods sold in association with the applied-for Mark in accordance with the provisions of section 50 of the Act. As it will become apparent, the Mark has never appeared alone on the cigarettes packs but always in combination with the VOGUE trade-mark. The license agreement expressly includes terms that compel the licensee to manufacture, label and package the goods bearing the VOGUE trade-mark strictly in accordance with the licensor’s specifications and standards, to submit production materials used in the manufacture of the relevant goods to the licensor for approval, to submit samples of final products to the licensor for approval, etc. For example, section 5.3 of the license agreement expressly provides that:

Before advertising, promoting or marketing the Products, the Licensee shall submit to the Licensor details of its proposals including samples of any Associated Products and examples of any advertising and promotional material to be used and the Licensor shall have the absolute right to prohibit the use of all or any part of such material which does not meet with its approval.

[30]

In this regard, Mr. Dacayanan confirmed in his cross-examination that before the launch of the Mark, the team he was working on needed “approval from the president of ITPL who at the same time [was] also the vice president marketing of [ITCan]” and that it is part of their “day to day that [they] keep [their] vice president up to date with projects” [Cross-examination transcript, p. 47, Q. 166]. I further accept the Applicant’s submission made at the hearing that the Applicant may have elected to wait for the Mark to mature to registration before amending the license agreement.

[31]

To conclude on this point, I will not make any negative inference from the fact that the Mark was not expressly identified in the license agreement.

[32]

Reverting to Mr. Dacayanan’s affidavit, Mr. Dacayanan asserts that the VOGUE Superslims family of cigarettes was launched by ITCan in August 2011, along with a marketing campaign that “included a new colour palette which focused on the colour purple.” He asserts that “as part of this campaign was the launch of the VOGUE Superslims cigarettes which are sold in a purple package (hereinafter the ‘PURPLE PACKAGE’)” [paras 4 and 5]. As Mr. Dacayanan thereafter refers throughout his affidavit to this product as the “PURPLE PACKAGE”, I will do the same while reviewing his affidavit.

[33]

In support, Mr. Dacayanan provides the following exhibits to his affidavit:

Exhibit B: Photographs of packages of VOGUE Superslims cigarettes sold in the PURPLE PACKAGE in Canada.

Exhibit B.1: VOGUE Superslims cigarettes sold in Canada in the PURPLE PACKAGE from August 2011 until March 2012.

Exhibit B.2: VOGUE Superslims cigarettes sold in Canada in the PURPLE PACKAGE from March 2012 until the date of swearing his affidavit.

[34]

The difference between Exhibits B.1 and B.2 resides in the percentage of the surface of the package covered by the mandatory health warnings (on at least 50% of the package from August 2011 until March 2012 and on at least 75% of the package since March 2012).

[35]

Mr. Dacayanan further explains that the VOGUE Superslims cigarettes sold in the PURPLE PACKAGE are part of the VOGUE Superslims family, which also includes a “variant” sold in a blue pack as well as a variant sold in a green pack [para 6].

[36]

Mr. Dacayanan asserts that “the colour purple for the VOGUE Superslims cigarettes sold in the PURPLE PACKAGE, and the use of the colour purple for promoting the VOGUE Superslims family of cigarettes, was used by ITPL and ITCan because it was considered to be highly distinctive, memorable, and eye-catching” and also because it “was not being used for the packaging of cigarettes by any other manufacturer, importer, or distributor of cigarettes in Canada at the time that the VOGUE Superslims cigarettes sold in the PURPLE PACKAGE were launched in August 2011” [para 7].

[37]

Mr. Dacayanan then turns to the sales of the VOGUE Superslims cigarettes in the PURPLE PACKAGE. He asserts that between August 2011 and the date of filing of the present statements of oppositions, ITCan “sold in excess of 980,000 packs of VOGUE Superslims cigarettes in the PURPLE PACKAGE to cigarettes retailers, distributors, and wholesalers in Canada, representing sales in excess of $4,800,000CAD” [para 8]. The table below sets out the yearly breakdown of the number of packs, and total sales amount of VOGUE Superslims cigarettes in the PURPLE PACKAGE in Canada between August 2011 and November 2014 [para 9].

| Year

|

Packs of Cigarettes (in excess of)

|

Sales Amount (in excess of)

|

| 2011

|

180,000

|

$875,000

|

| 2012

|

615,000

|

$3,000,000

|

| 2013

|

690,000

|

$3,400,000

|

| 2014 (YTD ending November)

|

675,000

|

$3,500,000

|

| TOTAL

|

2,150,000

|

$10,775,000

|

[38]

Mr. Dacayanan attaches as Exhibit C to his affidavit “copies of representative invoices of sales of VOGUE Superslims cigarettes in the PURPLE PACKAGE to various cigarette retailers in Canada” [para 10].

[39]

In the last part of his affidavit, Mr. Dacayanan turns to the permitted promotion of the VOGUE Superslims cigarettes in the PURPLE PACKAGE. He asserts that from August 2011 to May 23, 2013, ITCan has spent “in excess of one million dollars ($1,000,000CAD)” marketing the VOGUE Superslims family of cigarettes, including the VOGUE Superslims cigarettes in the PURPLE PACKAGE, to retailers and adult smokers in Canada, using materials “that focus on the colour purple” [para 11].

[40]

Mr. Dacayanan asserts that “as part of [ITCan’s] efforts to communicate the availability of the VOGUE Superslims family of cigarettes to adult smokers, ITCan used a variety of communication materials” which displayed the colour purple “as is used on the PURPLE PACKAGE” [para 12]. In support, Mr. Dacayanan provides the following exhibits to his affidavit:

Exhibit D: Examples of posters used by ITCan as part of the VOGUE Superslims marketing campaign from 2011-2012. Mr. Dacayanan asserts that “such posters were displayed in over one hundred (100) locations in Canada” from October to December 2011 and from January to March 2012 [para 12].

Exhibit E: Examples of trade communications distributed by ITCan in 2011-2012 to retailers and wholesalers in Canada, namely examples of backroom posters [Exhibit E.1] and examples of scan sheets displayed only to retailers/wholesaler employees [Exhibit E.2]. Mr. Dacayanan asserts that ITCan distributed trade communications featuring the PURPLE PACKAGE to over 8,500 of its retailers in Canada in 2011 and to almost 5,000 more in 2012 [paras 12 and 13].

The Dinelle affidavit

[41]

Mr. Dinelle attaches as Exhibit A to his affidavit a copy of the December 6, 2000 practice notice entitled “Three-dimensional Marks” (Practice Notice on Three Dimensional Marks) that he located on the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO) website.

The Owens affidavit

[42]

Ms. Owens attaches as Exhibit A to her affidavit details of the following 10 trade-mark registrations for colour marks for various products owned by third parties which she printed from the CDName Search Corp system on December 23, 2014:

| Trade-mark

|

Registration No.

|

| BLUE “COLOUR” DESIGN

|

TMA522,834

|

| BLUE (COLOUR) LOGO

|

535,786

|

| COLOUR – YELLOW

|

604,888

|

| Colour Mark (GREEN)

|

604,887

|

| COLOUR ORANGE DESIGN

|

616,900

|

| GREEN COLOUR LOGO

|

777,260

|

| ORANGE DESIGN

|

576,619

|

| Package Design

|

679,037

|

| PINK (COLOUR)

|

574,625

|

| YELLOW COLOUR

|

733,458

|

analysis

Section 30 grounds of opposition

[43]

The Opponent has pleaded multiple grounds of opposition under section 30 of the Act, many of which are redundant or overlap with one another. The material date to assess all of these grounds is the filing date of the applications [Georgia-Pacific Corp v Scott Paper Ltd (1984), 3 CPR (3d) 469 (TMOB)].

[44]

As set out in the 226 Decision, supra, at paragraph 30, the legal burden on the Applicant to show that each of its applications complies with section 30 includes both the question as to whether or not the Applicant has filed applications which comply with the formal requirements of the content of a trade-mark application and the question as to whether or not the statements contained in the applications are correct.

[45]

Before assessing in more detail some of the section 30 grounds pleaded by the Opponent, I wish to summarize below a few general principles governing the registration of colour marks that have guided me in the present cases.

General principles governing the registration of colour marks

[46]

According to the case law and CIPO’s position, it is possible to register a colour (or a combination of colours) applied to a particular item either as an “ordinary” trade-mark or as a “distinguishing guise” (in which colour forms an integral part of the mode of wrapping or packaging of the goods) [Smith, Kline & French v Registrar, [1987] 2 FC 633; Simpson Strong-Tie Co v Peak Innovations Inc [2007] TMOB No. 175, aff’d 2009 FC 1200, aff’d 2010 FCA 277; ORANGE Decisions, supra; and Practice Notice on Three Dimensional Marks]. The distinction between colour functioning as an ordinary trade-mark and not just a distinguishing guise is important as it impacts the examination stage of the application (per section 13(1) of the Act, an applicant is requested to provide evidence establishing that the distinguishing guise had already become distinctive at the time of the application for registration, whereas no equivalent provision applies to a colour mark as an ordinary trade-mark, which is not examined for distinctiveness – rather, a third party has to take steps to oppose such an application in order to challenge its distinctiveness during the registration process) and depends on how colour is claimed in the description of the mark in the application.

[47]

Section 28 of the Trade-mark Regulations (the Regulations) provides that where the applicant claims a colour as a feature of the trade-mark, that the colour be described and that such description be clear. Where the description is not clear, the Registrar may require the applicant to file a drawing lined for colour in accordance with a colour chart. There is no requirement in the Act or the Regulations that the applicant specifically reference the shade or hue of the color claimed [Novopharm Ltd v Pfizer Products Inc, 2009 CarswellNat 4119 (TMOB) at para 23; 226 Decision, supra, at para 46].

[48]

Likewise, section 30(h) of the Act provides that the application shall contain “…a drawing of the trade-mark and such number of accurate representations of the trade-mark as may be prescribed.” The drawing must be a meaningful representation of the trade-mark in the context of the written description appearing in the application and must enable the determination of the limits of the trade-mark; the rationale behind these requirements is that a trade-mark registration is a monopoly and must therefore, be precise in terms of its scope [Apotex Inc v Searle Canada Inc (2000), 6 CPR (4th) 26 (FCTD) at para 7; and Novopharm Ltd v Astra Aktiebolag (2000) 6 CPR (4th) 16 (FCTD)]. There is no requirement for the applicant to restrict the trade-mark claimed to a specific size, so long as the goods are adequately described and defined [Simpson Strong-Tie, supra, at p 57; 226 Decision, supra, at paras 36-37; Apotex Inc v Searle Canada Inc, supra].

[49]

A colour that is primarily functional from either an ornamental or a utilitarian point of view is not registrable [Procter & Gamble Inc v Colgate-Palmolive Canada Inc (2007), 60 CPR (4th) 62 (TMOB), aff’d 81 CPR (4th) 343 (FC) at para 53; Practice Notice on Three-dimensional Marks].

[50]

Applying these principles to the present cases, I propose to address the section 30 grounds of opposition pleaded by the Opponent under two main themes, namely (i) whether or not the Applicant has filed applications which comply with the formal requirements of the content of a trade-mark application; and (ii) whether or not the statements contained in the applications are correct.

Do the applications comply with the formal requirements of the content of a trade-mark application?

[51]

As per the details reproduced in Schedules A and B, the Opponent has pleaded that the applications do not formally comply with the requirements of section 30 of the Act for a number of “technical” reasons relating to both the description and the drawing per se of the Mark. While not always expressly referred to in the Opponent’s pleading, these grounds fall under section 30(h) of the Act.

[52]

For the reasons that follow, I find that the applications do comply with the formal requirements of section 30(h) of the Act in that the drawing and description make it clear that the applied-for Mark is not a distinguishing guise but rather is an “ordinary” trade-mark consisting of a single colour applied to the visible surface of two- and three-dimensional representations of cigarette packaging.

[53]

As mentioned above, the '250 Application and '255 Application are substantively identical in terms of the manner of depiction and description of the applied-for trade-mark (other than the colour claimed and specific shape depicted) to application Nos. 1,317,128 and 1,317,127 respectively, discussed at length in the ORANGE Decisions, supra [see, inter alia, paras 32-38, and 51-59 of the 226 Decision, supra; and paras 26-51 of the FC 608 Decision, supra]. I see no reason to depart from the findings made by the Registrar and the Federal Court in those decisions.

[54]

As was the case with application No. 1,317,127, the drawing and description included in the '255 Application clearly set out in dotted outline the surface of the particular package to which the colour claimed in the application is to be applied. Transposing the comments of Board Member Folz at paragraph 37 of the 226 Decision, supra, to the present case, the Applicant is not claiming the cigarette packaging as its trade-mark but employing the appearance of part of what I consider to be a standard rectangular shaped cigarette package to show that it is limiting the scope of its claim to the colour purple to one panel of the packaging. In other words, and as stressed by the Applicant, the mere reference to the word “packaging” in the application does not transform the present application from an ordinary trade-mark application into one for a distinguishing guise. The drawing of the Mark is also in compliance with the Practice Notice on Three-Dimensional Marks which states that “where an application is for a two-dimensional mark, the drawing of the mark should show the mark in isolation and should not show the mark as applied to a three-dimensional object.” Further, as indicated above, there is no requirement for the Applicant to restrict the applied-for Mark to a specific size.

[55]

Transposing the comments of Board Member Folz at paragraph 38 of the 226 Decision, supra, the same reasoning applies with respect to the '250 Application, with the main exception being that, as a three-dimensional mark, the drawing and description clearly show that the colour purple is applied to the front, back and side of the cigarette packaging that has width, height and depth as opposed to the applied-for mark in the '255 Application which applies to only one panel of the packaging which is two-dimensional. The Applicant does not seek to protect the shape of the cigarette packaging but rather seeks to protect the application of the colour purple as applied to that cigarette packaging. The drawing and description for the Mark in the '250 Application are also in compliance with the Practice Notice on Three-Dimensional Marks which requires that an application for a three-dimensional mark include a description of the mark that makes it clear that the mark applied for is a three-dimensional mark. The description “…the trade-mark consists of colour purple applied to the visible surface of the particular packaging as shown in the attached drawing”, with a three dimensional drawing showing the relative width, height and depth of the packaging, does so. In fact, this description essentially matches the one provided in the practice notice as an “example of an acceptable description” of a trade-mark “that [is] not [a] distinguishing guis[e], that [is] not two dimensional and that consist[s] of or include[s] one or more colours applied to the surface of a three-dimensional object”, namely: “The trademark consists of the colour purple applied to the whole of the visible surface of the particular tablet shown in the drawing.”

[56]

Furthermore, a parallel can be made between the present applications and the various third party registrations for ordinary trade-marks having an identical structure to that of the applied-for Mark introduced into evidence by the Owens affidavit. I agree with the Applicant that such evidence is persuasive evidence in that it would be fundamentally inequitable to the Applicant to hold that the Mark is not properly depicted as a trade-mark [Rothmans, Benson & Hedges Inc v RJ Reynolds Tobacco Co (1993), 47 CPR (3d) 439 at 442-443(FCTD); FC 608 Decision, supra, at para 37].

[57]

In view of all the foregoing, the grounds of opposition set out in paragraphs 5(d), 7, 8 and 9 of the statement of opposition are dismissed in both cases.

Are the statements contained in the applications correct?

[58]

As per the details reproduced in Schedules A and B, the Opponent has pleaded at paragraph 5 of its statement of opposition, that the applications do not comply with the requirements of section 30 of the Act because the applied-for Mark is not a trade-mark and/or has not been used as a trade-mark within the meaning of section 2 of the Act and as claimed in the applications, for a number of reasons. As the present applications are based on use of the applied-for Mark, and except for the ground of opposition pleaded at paragraph 5(d) which more appropriately falls under section 30(h) of the Act, I consider these grounds of opposition to fall under section 30(b) of the Act; the rationale being that an application based on use of a trade-mark since a claimed date of first use cannot comply with section 30(b) of the Act if the trade-mark that has been used is not a trade-mark or the trade-mark applied-for. I further note that the Applicant has not questioned the sufficiency of the Opponent’s pleadings.

[59]

The Opponent has also pleaded at paragraph 6(a) of its statement of opposition that the applications do not comply with the requirements of section 30(b) of the Act because the applied-for Mark has not been used in Canada as of the claimed date of first use in that at the time of transfer of the property in or possession of the goods in the ordinary course of trade, the applied-for Mark is not visible in the manner claimed in the applications to the persons to whom the property in or possession of the goods is transferred. Alternatively, the Opponent has pleaded that if the applied-for Mark is visible, it is not marked on the goods or otherwise so associated with the goods that notice of the association is then given to the persons to who the property is transferred, for the reasons described in paragraph 6(b) of its statement of opposition.

[60]

To the extent that the relevant facts pertaining to a ground of opposition based on section 30(b) of the Act are more readily available to the Applicant, the evidential burden on the Opponent with respect to such a ground of opposition is less onerous [see Tune Master v Mr P’s Mastertune Ignition Services Ltd (1986), 10 CPR (3d) 84 (TMOB)]. Furthermore, this burden can be met by reference not only to the Opponent’s evidence but also to the Applicant’s evidence [see Labatt Brewing Company Limited v Molson Breweries, a Partenership (1996), 68 CPR (3d) (FCTD) 216]. However, the Opponent may only successfully rely upon the Applicant’s evidence to meet its initial burden if the Opponent shows that the Applicant’s evidence puts into issue the claims set forth in the Applicant’s applications [see Corporativo de Marcas GJB, SA de CV v Bacardi & Company Ltd 2014 FC 323 at paras 30-38 (CanLII)].

[61]

Addressing first the fact that the colour purple is not visible in the manner claimed in the applications because it has actually occupied only fractional parts of various panels of the VOGUE Superslims cigarette packaging due to the presence of mandatory health warnings that cover a percentage of such cigarette packaging (as shown in Exhibits B.1 and B.2 to the Dacayanan affidavit), this does not render the use statements contained in the Applicant’s applications incorrect.

[62]

The tobacco industry does not operate in isolation but is highly regulated. The present applications cover “the colour purple applied to the visible surface of the particular packaging as shown in the [accompanying] drawing” [my emphasis]. That visible surface corresponds in fact to the entire surface of the package permissible by law as evidenced by the Dacayanan affidavit, which demonstrates that the Applicant has applied the colour purple as claimed to the entire surface of the package that it has been permitted by law to brand. By referring to the visible surface of the packaging rather than the entire surface thereof, the description of the Mark takes into account the fact that parts of the packaging may be blocked out or covered by evolving mandatory health warnings that preclude the application of the claimed colour to the entire surface of the packaging. Furthermore, as noted by the Federal Court of Appeal in the 111 decision, supra, consumers will understand that health warnings on a cigarette package are not part of the trade-mark. This brings me to turn to the other markings and indicia of source appearing on the Applicant’s cigarette packaging.

[63]

There is no dispute that the Mark has never appeared alone on the cigarette packs but always in combination with the VOGUE word and design marks.

[64]

As reminded by the Applicant, it is well established that multiple trade-marks may be used together on the same product [AW Allen Ltd v Warner Lambert Canada Inc (1985), 6 CPR (3d) 270 at 272 (FCTD)]. However, whether the use of any alleged trade-mark in combination with other matter constitutes use as a trade-mark is a question of fact: use of any alleged trade-mark in combination with other matter only constitutes use as a trade-mark if the public, as a matter of first impression, perceives the alleged trade-mark as being used as a trade-mark [Nightingale Interloc v Prodesign Ltd (1984), 2 CPR (3d) 535 (TMOB) at paras 7-8].

[65]

In this regard, I cannot but agree with the Applicant that some parallels can be made between the present cases and the ORANGE Decisions wherein Board Member Folz noted that the Applicant’s cigarette packages also showed the use of other markings and indicia of source appearing on the ORANGE PACKAGE DESIGN, namely the marks PETER JACKSON and the unicorn design. In its appeal before the Federal Court of Appeal, the Opponent had argued, as in the present cases, that Member Folz failed to properly consider and refer to the principles enunciated in Nightingale, supra, in her assessment of the section 30 grounds of opposition pleaded by the Opponent. In dismissing the appeal, the Court found that on a fair reading of Member Folz’ s reasons, it was clear that she turned her mind to these issues and addressed them in substance at paragraphs 42 and 46 of her reasons, reproduced below:

42. Again, no arguments have been put forth by the Opponent in support of this ground [section 30(b) of the Act]. In any case, having had regard to the evidence as filed, I note that there is nothing in the Applicant’s evidence that is clearly inconsistent with its claimed date of first use. As shown in the evidence of Mr. Bussey, between April 2006 and August 14, 2007, ITCan sold approximately 9-11 million packs of Peter Jackson “Smooth Flavour” cigarettes in association with the Marks to cigarette retailers, distributors and wholesalers in Canada, representing sales in excess of $34 million Canadian. The evidence also shows that the Applicant has provided notification to the public of its claim that the colour orange is its trade-mark. In this regard, the Applicant engaged in an extensive marketing campaign to communicate the availability of the Peter Jackson Smooth Flavour cigarettes to both cigarette retailers and adult smokers in Canada focusing on the colour orange and highlighting the orange package design (Bussey, paras. 9-11; Exhibit C and D). Further, the Applicant’s evidence shows the colour orange as applied to the front, back and sides of its cigarette packages. The fact that the Applicant’s cigarette packages must also contain a health warning that covers 50% of the principal face of the package of cigarettes does not, in my view, affect the Mark’s ability to distinguish the Applicant’s wares from those of others. On a related note, while the Applicant’s cigarette packages may also show the use of the marks PETER JACKSON and the unicorn design, it is well established that multiple trade-marks may be used together on the same product [see AW Allen Ltd. v. Warner Lambert Canada Inc. (1985), 6 CPR (3d) 270 at 272 (FCTD) (AW Allen)]. Finally, as the bans on retail displays of tobacco products were not in place throughout Canada as of the material date for this ground, the Mark was visible to the consumer prior to the time of transfer of the goods. I note that even if the Mark had not been visible to the consumer prior to the time of transfer, it still would have been visible to the consumer when the consumer purchased the cigarette wares (i.e. at the time of transfer).

[…]

46. First, I note that no evidence has been adduced by the Opponent to support the allegations set forth in its statement of opposition that the Mark is ornamental in nature [Dot Plastics Ltd. v. Gravenhurst Plastic Ltd. (1988), 22 CPR (3d) 228 (T.M.O.B.) and Procter & Gamble Inc. v Colgate-Palmolive Canada Inc. (2007), 60 CPR (4th) 62 (TMOB); aff’d 2010 FC 231 (CanLII), 81 CPR (4th) 343 (FC)]. Further, I note that there is no requirement in the Act or the Trade-mark Regulations that the Applicant specifically reference the shade or hue of the claimed colour orange [Novopharm Ltd. v. Pfizer Products Inc. 2009 CarswellNat 4119 (TMOB) at para 23; Section 28 of the Trade-mark Regulations], nor the specific dimensions of the size or shape of the trade-mark [see Simpson Strong-Tie, supra]. Finally, in view that there is nothing to prevent the Applicant from using more than one mark at the same time [AW Allens, supra], the fact that the Applicant uses other trade-marks in association with its cigarette wares does not, in my view, support the argument that the Mark is not associated with the wares at the time of transfer.

[66]

The Court found that Member Folz referred to relevant evidence submitted by the Applicant “and in particular how it had notified the public that the colour orange was used as its trade-mark”, and that she “was satisfied that the public would perceive the applied-for marks per se as trade-marks and that the evidence demonstrated use of those trade-marks per se by the [Applicant]”. The Court further found that Member Folz also noted that the Opponent had adduced no evidence to support its allegation that the marks were merely ornamental. As a result, the Court was not persuaded that the Registrar’s decision was unreasonable.

[67]

This brings me to turn to how the Applicant has “notified the public” that the colour purple was used as its trade-mark as opposed to being merely ornamental, in light of some of the arguments put forward by the parties.

[68]

First, I note that the mere fact that the Applicant may have been the first to use the colour purple on cigarette packaging does not itself imply that it has led to a distinct brand identity and the public recognition of the PURPLE PACKAGE DESIGN as a trade-mark in and of itself. Indeed, in Royal Doulton Tableware Ltd v Cassidy’s Ltd (1986), 1 CPR (3d) 214 (FCTD), the Federal Court explains that a trade-mark may be recognized as unique but not be distinctive:

It is to be noted that a distinctive trade mark is one which links, e.g., goods with a vendor so as to distinguish them from the goods of other vendors. It is not distinctive if it simply distinguishes one design of goods from another design of goods even though if one had special trade knowledge one might know that these two kinds of goods are sold respectively by two different vendors. Such a concept of distinctiveness would run counter to a basic purpose of the trade mark which is to assure the purchaser that the goods have come from a particular source in which he has confidence. See Fox, Canadian Law of Trade Marks and Unfair Competition (3rd ed., 1972) at pp. 25-26

[69]

Furthermore, while the Applicant contends that it engaged in an extensive marketing campaign to communicate the availability of the VOGUE Superslims cigarettes to both cigarette retailers and adult smokers in Canada focusing on the colour purple and highlighting the PURPLE PACKAGE DESIGN, a review of the marketing materials exhibits attached to the Dacayanan affidavit reveals, in my view, a different reality.

[70]

Indeed, as per the example of scan sheet attached as Exhibit E.2 to the Dacayanan affidavit reproduced at Schedule C to my decision, the “purple” VOGUE Superslims cigarette packaging is featured side-by-side with the “blue” and “green” variants of the Applicant’s VOGUE Superslims cigarettes, along with a brief description of their associated flavours or “strength” (the blue packaging corresponding to “a full yet refined taste”; the purple packaging to “a subtle yet satisfying taste”, and the “green” one to “a full taste with crisp menthol flavor”). As per the legend at the bottom of the sheet, the phrase “ONE OF A KIND*” refers to the “unique curved pack structure” of all three cigarette packages of the VOGUE Superslims family of cigarettes, rather than highlighting the PURPLE PACKAGE DESIGN per se. Furthermore, it is difficult to conceive how the faded coloured image of building facades in the upper right portion of the sheet could be perceived otherwise than merely as an aesthetic background.

[71]

Likewise, the backroom poster attached as Exhibit E.1 to the Dacayanan affidavit also reproduced hereto at Schedule C, which displays the partial image of a woman whispering the message “I can’t tell you…Yet I can hardly wait”, merely announces that “A dazzling change is coming soon from Vogue Superslims”. Not only is the PURPLE PACKAGE DESIGN not reproduced on the poster, it is also not even alluded to.

[72]

Finally, the examples of posters attached as Exhibit D to the Dacayanan affidavit, an example of which is also reproduced hereto at Schedule C, all focus on the pack structure of the packaging of the VOGUE Superslims family of cigarettes. The “purple” VOGUE Superslims cigarette packaging is, here again, displayed together with the “blue” and “green” variants of the Applicant’s VOGUE Superslims cigarettes. While dark shades of the colour purple appear in background, it is difficult to conceive how such colour gradient could be perceived otherwise than merely as an aesthetic background, especially in view of the fact that the ad does not pertain only to the “purple” variant of the VOGUE Superslims cigarettes, let alone the PURPLE PACKAGE DESIGN in and of itself.

[73]

In this regard, I note that the Applicant, both in its written argument and at the hearing, insisted on the fact that one of the reasons why the colour purple was selected by the Applicant is because it would have allegedly never been used before contrary to “conventional cigarette package colours such as green and blue” that “had been use before”/ “have been around forever”. However, as the very same “get-up” (except for the colour applied to the cigarette packaging) has been used by the Applicant for all three cigarette packaging products/variants comprising the VOGUE Superslims family, I fail to understand on what basis the public would have considered or perceived the colour purple applied to the packaging of the “subtle taste” variant as a trade-mark in and of itself (i.e. indicator of source), while at the same time treating differently the colours “blue” and “green” applied to the packaging of the “full taste” and “menthol taste” variants respectively of the VOGUE Superslims family of cigarettes.

[74]

Thus, I find the evidence is far from establishing that the Applicant has provided notification to the public of its claim that the colour purple as applied to the packaging of one of the variants of the VOGUE Superslims family of cigarettes is its trade-mark. To the contrary, the fact that the “purple” VOGUE Superslims packaging has always been featured side-by-side with the “green” and “blue” variants of the VOGUE Superslims family of cigarettes in the Applicant’s advertising and promotional materials gives the impression that the Applicant’s use and adoption of the colour purple was not for trade-mark purposes, but rather for differentiating between flavours or “strengths” of the same type of cigarette product.

[75]

In this regard, I acknowledge that the Trial Division of the Federal Court held in Santana Jeans Ltd v Manager Clothing Inc (1993), 52 CPR (3d) 472, that some degree of ornamentation does not preclude registrability when the trade-mark in issue also has distinctive features. However, for the reasons set out above, I find the evidence led in the present cases does not support the position that the colour purple served a dual purpose here, namely operating both as a trade-mark in and of itself, and serving as an aesthetics background colour distinguishing between the various product lines of the VOGUE Superslims family of cigarettes. To the contrary, I find the Applicant’s evidence seriously and directly puts into issue the correctness of the claims set forth in the Applicant’s applications. Therefore, I am not satisfied that the Applicant has established, on a balance of probabilities, that it had used the PURPLE PACKAGE DESIGN as a trade-mark since the claimed date of first use, as of the filing date of both of its applications, and the grounds of opposition set out in paragraphs 5(b) and 6(b) of the statement of opposition succeed in both cases.

[76]

If I am wrong in assessing the functionality and ornamental nature of the Mark in light of the evidence of use of record, rather than considering the Mark as applied for “in abstracto”, or else, if the colour purple could in fact serve a dual basis here, I would still find that the Applicant’s evidence seriously and directly puts into issue the correctness of the claims set forth in the Applicant’s applications, specifically that the applied-for Mark is not marked on the Goods, for the following reasons.

[77]

As per my review above of Exhibits D and E attached to the Dacayanan affidavit, there is no such thing as a purple family of VOGUE Superslims cigarettes. What the evidence shows here is the existence of a VOGUE Superslims family of cigarettes varying in strength or flavour, that comes in three colours, and sharing a unique curved pack structure. At best for the Applicant, I find that the colour purple could be perceived simply as a background colour that is part of a composite trade-mark comprising the VOGUE word and design marks. In this regard, upon my reading of the ORANGE Decisions, I find the facts of the present cases can seemingly be distinguished from those in the ORANGE Decisions where the Registrar was satisfied, by reason of the Applicant’s extensive marketing campaign focusing on the colour orange and highlighting the orange package design per se, that the public would have perceived the orange package design per se as the trade-mark being used, despite being also used in combination with the marks PETER JACKSON and the unicorn design.

[78]

In view of the foregoing, I am not satisfied that the Applicant has established, on a balance of probabilities, that it had used the PURPLE PACKAGE DESIGN as a trade-mark since the claimed date of first use, as of the filing date of both of its applications and the ground of opposition set out in paragraph 5(e) of the statement of opposition succeeds in both cases.

Remaining grounds of opposition

[79]

Having already determined that the Opponent was successful on more than two grounds of opposition, I do not find it necessary to discuss the remaining grounds of opposition.

Disposition

[80]

Pursuant to the authority delegated to me under section 63(3) of the Act, I refuse both applications pursuant to section 38(8) of the Act.

|

|

| Annie Robitaille

|

| Member

|

| Trade-marks Opposition Board

|

| Canadian Intellectual Property Office

|

Schedule A

Excerpts from the statement of opposition filed in respect of the '250 Application

“4. The Opponent bases its opposition on the grounds of opposition set out below.

Section 38(2)(a) and Section 30

5. The Opponent bases its opposition on the ground provided by paragraph 38(2)(a) of the Act in that the Application does not conform to the requirements of section 30 of the Act. In particular, section 30 provides that the Applicant must be applying to register a "trade-mark". The alleged trade-mark depicted and described in the Application is not a "trade-mark" within the meaning of section 2 of the Act for the following reasons:

a. Under section 2 of the Act, a trade-mark is defined as a mark that is used for the purpose of distinguishing or so as to distinguish an applicant's wares from those of others;

b. The alleged trade-mark, namely the colour purple as applied to the claimed packaging, is merely ornamental and is not, nor can it function as, a trade-mark as defined by the Act;

c. The alleged trade-mark is merely an ornamental colour alone without defining with any specificity the associated size or shape of the trade mark, or alternatively, the alleged trade-mark is merely an ornamental colour in association with a common shape. In either case, the alleged trade-mark is not, nor can it function as, a trade-mark as defined by the Act;

d. The alleged trade-mark as described and depicted in the Application is vague and imprecise, there being no specific reference to the shade or hue of the claimed colour purple; and

e. At the time of transfer in the property of the wares, the alleged trade-mark is not marked on the wares or otherwise so associated with the wares that notice of the association is then given to the person to whom the property is transferred, as the alleged trade-mark is simply the colour of a commonly shaped package on which other markings and indicia of source appear.

6. The Opponent bases its opposition on the ground provided by paragraph 38(2)(a) of the Act in that the Application does not conform to the requirements of section 30(b) of the Act. The alleged trade-mark has not been used in Canada as of the date claimed in the Application in association with the wares referred to in the Application, including in that:

a. At the time of transfer of the property in or possession of the wares in the ordinary course of trade, the alleged trade-mark is not visible in the manner claimed in the Application to the persons to whom property in or possession of the wares is transferred; and

b. Alternatively, if the alleged trade-mark is visible at the time of transfer in the property of the wares, the alleged trade-mark is not marked on the wares or otherwise so associated with the wares that notice of the association is then given to the person to whom the property is transferred, as the alleged trade-mark is simply the colour of a commonly shaped package on which other markings and indicia of source appear. Consumers are generally familiar with different coloured packaging for manufactured tobacco products and consider the colour of the packaging as claimed to be a merely ornamental component of the packaging as opposed to a distinct trade-mark associated with the wares. The colour purple as claimed in the Application is not indicative of source.

7. The Opponent bases its opposition on the ground provided by paragraph 38(2)(a) of the Act in that the Application does not conform to the requirements of section 30(h) of the Act. The Application does not contain an accurate drawing and representation of the alleged trade-mark. The drawing filed with the Application does not properly define the limits of the trade-mark monopoly. The Application does not contain a sufficient number of accurate representations so as to set out all features of the alleged trade-mark.

8. In addition, the drawing does not accurately represent the alleged trade-mark, as there is no definition to the size or dimensions of the ‘package’, with the result that the Application is simply an application to register a colour alone without association to a defined shape or size of package.

9. Lastly, the drawing and description of the alleged trade-mark clearly show that the subject matter for which registration is sought is a distinguishing guise (as defined by section 2 of the Act) and the Application should have been filed as such. The requirements of section 13 of the Act have not been met.

10. The Opponent bases its opposition on the ground provided by paragraph 38(2)(a) of the Act in that the Application does not conform to the requirements of section 30(i) of the Act. At the date of filing, or any other material time, the Applicant could not have been satisfied it was entitled to use the alleged trade-mark in Canada in association with the wares specified in the Application. The Applicant was aware that the alleged trade-mark was not a trade-mark for the reasons outlined above.

11. In addition, the Applicant was also aware that any grant to the Applicant of exclusivity in the use of the colour 'purple' as claimed is contrary to public policy as leading to an exhaustion of the colour availability to others.

Section 38(2)(b) and Sections 12 and 13

12. The Opponent bases its opposition on the ground provided by paragraph 38(2)(b) of the Act in that the alleged trade-mark is not registrable. If the alleged trade mark is a trade-mark at all, which is denied, it is a distinguishing guise as defined in section 2 of the Act and as such, it is not registrable pursuant to section 12 because the requirements of section 13 of the Act have not been met. The alleged trade-mark relates to the mode of wrapping or packaging of the wares.

[…]

Section 38(2)(d) and Section 2

14. The Opponent bases its opposition on the ground provided by paragraph 38(2)(d) of the Act in that the alleged trade-mark is not distinctive within the meaning of section 2 of the Act. That is, the alleged trade-mark cannot distinguish, nor is it adapted to distinguish, the wares in association with which it has allegedly been used in Canada, from the wares of others, including those of the Opponent. More particularly, the alleged trade-mark cannot be distinctive of the Applicant as:

a. The alleged trade-mark is merely ornamental and cannot inherently function as a trade-mark;

b. The alleged trade-mark is incapable of functioning as a trade-mark as it is not marked on the wares or otherwise so associated with the wares that notice of the association is then given to the person to whom the property is transferred, as the alleged trade-mark is simply the colour of a commonly shaped package on which other markings and indicia of source appear, and therefore, does not actually distinguish the wares in association with which it is used by the Applicant from the wares of others, nor is it adapted so to distinguish them;

c. The alleged trade-mark is incapable of functioning as a trade-mark as the representation and description of the alleged trade-mark is vague and imprecise, not being limited by reference to a specific shade or hue of the colour purple, and therefore, does not actually distinguish the wares in association with which it is used by the Applicant from the wares of others, nor is it adapted so to distinguish them;

[…]”

Schedule B

Excerpts from the statement of opposition filed in respect of the '255 Application

[Only the section 30 grounds of opposition that differ in content from those reproduced in Schedule A in respect of the '250 Application are hereinafter reproduced]

“4. The Opponent bases its opposition on the grounds of opposition set out below.

Section 38(2)(a) and Section 30

5. The Opponent bases its opposition on the ground provided by paragraph 38(2)(a) of the Act in that the Application does not conform to the requirements of section 30 of the Act. In particular, section 30 provides that the Applicant must be applying to register a ‘trade-mark’. The alleged trade-mark depicted and described in the Application is not a ‘trade-mark’ within the meaning of section 2 of the Act for the following reasons:

[…]

c. The alleged trade-mark is merely an ornamental colour alone without defining with any specificity the associated size or shape of the trade mark, or alternatively, the alleged trade-mark is merely an ornamental colour in association with a common shape. The Application refers to but does not disclose any ‘particular packaging’ and fails to disclose any shape of packaging that might be capable of distinguishing the Applicant's wares from the wares of others. In either case, the alleged trade-mark is not, nor can it function as, a trade-mark as defined by the Act;

[…]

e. At the time of transfer in the property of the wares, the alleged trade-mark is not marked on the wares or otherwise so associated with the wares that notice of the association is then given to the person to whom the property is transferred, as the alleged trade-mark is simply the colour of a common shape that is the face of a package on which other markings and indicia of source appear.

6. The Opponent bases its opposition on the ground provided by paragraph 38(2)(a) of the Act in that the Application does not conform to the requirements of section 30(b) of the Act. The alleged trade-mark has not been used in Canada as of the date claimed in the Application in association with the wares referred to in the Application, including in that:

[…]

b. Alternatively, if the alleged trade-mark is visible at the time of transfer in the property of the wares, the alleged trade-mark is not marked on the wares or otherwise so associated with the wares that notice of the association is then given to the person to whom the property is transferred, as the alleged trade-mark is simply the colour of a common shape that is the face of a package on which other markings and indicia of source appear. Consumers are generally familiar with different coloured packaging for manufactured tobacco products and consider the colour of the packaging as claimed to be a merely ornamental component of the packaging as opposed to a distinct trade-mark associated with the wares. The colour purple as claimed in the Application is not indicative of source.”

Schedule C

Excerpt from Exhibit E.2 to the Dacayanan affidavit

Excerpt from Exhibit E.1 to the Dacayanan affidavit

Excerpt from Exhibit D to the Dacayanan affidavit

TRADE-MARKS OPPOSITION BOARD

CANADIAN INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY OFFICE

APPEARANCES AND AGENTS OF RECORD

___________________________________________________

HEARING DATE 2018-07-11

APPEARANCES

| James Green

|

FOR THE OPPONENT

|

| Timothy Stevenson

|

FOR THE APPLICANT

|

AGENTS OF RECORD

| GOWLING WLG (CANADA) LLP

|

FOR THE OPPONENT

|

| SMART & BIGGAR

|

FOR THE APPLICANT

|